A TELEGRAM LED TO THE LIBERATION OF ROMA IN 1870, NO WONDER POPE PIUS IX CONDEMNED ALL TECHNOLOGICAL PROGRESS!! |

After the epochal telegram sent by Professor Morse in 1844, the second most important telegram was the Ems telegram sent by King Wilhelm I of Prussia to Chancellor Bismarck!

Bad

(spa) Ems, Germany.

|

|

Memorial stone to the Ems telegram, Bad Ems, Germany. |

By 1870, France had 3 reasons for going to war with Prussia:

| 1 | In

1866, Prussia defeated French ally Austria at the Battle of Sadowa. |

| 2 | In

1868, Spanish general Prim nominated a Prussian prince for the vacant

Spanish throne. |

| 3 | Spanish general Prim fought against French Marshal Bezaine in Mexico. |

Prussia knew that Emperor Napollyon III desperately wanted a war, but Prussia was not about to become the aggressor by firing the first shot.

The Ems telegram enraged France and Napollyon III opened hostilities by declaring war on Prussia.

The first telegram was a Bible verse about Israel

The first telegram sent via the newly invented miracle of the telegraph was a message about Israel....What Hath God Wrought! is a quote about Israel and JEHOVAH'S promise of Divine protection for His chosen people.

Most of the Christians in the New Jerusalem believed that they were Israel, commanded by the Almighty to build a GREAT nation in the wilderness:

Now JEHOVAH had said unto Abram (Abraham), Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father's house, unto a land that I will shew thee:

And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee, and make thy name great; and thou shalt be a blessing. And I will bless them that bless thee, and curse him that curseth thee: and in thee shall all families of the earth be blessed. (Genesis 12:1-3).

When the first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858, the Christians saw it as another miracle of Providence, and the means whereby the world would be united in peace and universal brotherhood.

Samuel F. B. Morse (1791–1872). |

|

Cyrus W. Field (1819–1892). |

Unfortunately, the most important link between the New Jerusalem and Russia was sabotaged!

When the first transatlantic link was completed in 1858, euphoria reigned in the United States; week long celebrations were held in New York and other cities. Many saw it as the coming of an era of peace on earth and goodwill toward all men:

To-morrow the hearts of the civilized world will beat to a single pulse, and from that time forth forevermore the continental divisions of the earth will in a measure lose those conditions of time and distance which now mark their relations one to the other. But such an event, like a dispensation of Providence, should be first contemplated in silence. (McDonald, A Saga of the Seas, p. 63).

Even the staid Times of London lauded it as the greatest feat of engineering of the century.

After the British refused to grant Morse a patent, he went to Paris and offered his invention to the French. He even told the minister of war, general Simon Bernard, that the first nation adopting his telegraph would be victorious in battle.

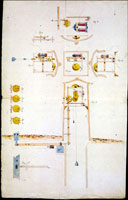

1838 railway telegraph drawing by Morse. |

|

General Simon Bernard (1779–1839). |

The French were also very reluctant to adopt this revolutionary invention.

Morse was also a great admirer of the French and General Lafayette was a close friend. The telegraph is absolutely necessary for the safe running of the railway system:

A week or two after I exhibited at my lodgings, in connection with this instrument, my railroad telegraph, an application of signals by sound, for which I took out letters patent in Paris, and at the same time I communicated to the Minister of War, General Bernard, my plans for a military telegraph with which he was much pleased.

I dined with him by invitation, and in the evening, repairing with him to his billiard-room, while the rest of the guests were amusing themselves with the game, I gave him a general description of my plan. He listened with deep attention while I advocated its use on the battlefield, and gave him my reasons for believing that the army first using the facilities of the electric telegraph for military purposes would be sure of victory. (Edward Lind Morse, Samuel F. B. Morse. His Letters and Journals, pp.132-133).

The general died the following year, and the French were as slow as the British to adopt this revolutionary technology. After President Lincoln, the Prussians were the first nation use this technology to great effect against the Austrians in 1866.

A Prussian prince for the vacant Spanish throne!!

Spain had a Glorious Revolution in 1868 when General Prim forced the dictatorial Queen Isabella II to resign.

General Prim and the new Spanish parliament offered the vacant throne to Leopold of the Prussian House of Hohenzollern.

His nomination enraged ex-queen Isabella . . . and she forced Napollyon III to have his nomination withdrawn.

Isabella II of Spain (1830–1904). Queen from 1833 to 1868. |

|

Queen Isabella in exile in Paris. |

Here is a list of the queen's pompous titles:

Isabella II, by the grace of God Queen of Castille, León, Aragon, the Two Sicilies, Jerusalem, Navarre, Granada, Toledo, Valencia, Galicia, Majorca, Seville, Sardinia, Córdoba, Corsica, Murcia, Minorca, Jaén, Algarve, Gibraltar, the Canary Islands, the Eastern and Western Indies, the Islands and Lands of the Ocean; Archduchess of Austria; Duchess of Burgundy, Brabant and Milan; Countess of Habsburg, Flanders, Tirol and Barcelona; Lady of Biscay and Molina, etc., etc.

The only place missing from that list . . . is the MOON!!

In September 1868, Queen Isabella was forced to abdicate and she went into exile in PARIS.

Statue of General Prim in Spain. |

|

Juan Prim was assassinated by the Jesuits in 1870. |

For the new constitutionally ruled Spain, General Prim offered the vacant throne to German Prince Leopold of the House of Hohenzollern.

This infuriated ex-queen Isabella . . . and Napollyon....Leopold was forced to withdraw his nomination, and King Wilhelm was pressured to give assurance in writing that his candidature, or any other Hohenzollern, would never again be considered for the vacant throne.

Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern (1835–1905). |

|

Princess

Antónia (1845–1913),

wife of Prince Leopold. |

The offer of the throne to a prince who would honor the Spanish constitution was totally anathema to Isabella and Napollyon.

Following protests by France, Wilhelm withdrew Leopold's name. This was considered a diplomatic defeat for Prussia. The French were not yet satisfied with this and demanded further commitments, especially a guarantee by the Prussian king that no member of any branch of his Hohenzollern family would ever be a candidate for the Spanish throne.

Prussian King Wilhelm (1797–1888). Reigned from 1861 to 1888. |

|

Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898). Chancellor of Germany from 1871 to 1890. |

Prussian King Wilhelm was also of the House of Hohenzollern. He refused to give the French assurance that his family would never again be candidates for the throne of Spain.

King Wilhelm and Count Benedetti. |

|

Count Benedetti (1817–1900). |

This conversation with the French ambassador, Count Benedetti, took place on July 13, 1870.

From the meeting, the king's secretary, Heinrich Abeken, wrote an account which was passed on to Otto von Bismarck in Berlin. Wilhelm described the French ambassador as "very inopportune" The King gave permission to Bismarck to release an account of the events to the press.

Text of the EMS Telegram

Sent by Heinrich Abeken of the Prussian Foreign Office under King Wilhelm's Instruction to Bismarck:

Count Benedetti intercepted me on the promenade and ended by demanding of me in a very importunate manner that I should authorize him to telegraph at once that I bound myself in perpetuity never again to give my consent if the Hohenzollerns renewed their candidature. I rejected this demand somewhat sternly as it is neither right nor possible to undertake engagements of this kind [for ever and ever]. Naturally I told him that I had not yet received any news and since he had been better informed via Paris and Madrid than I was, he must surely see that my government was not concerned in the matter. [The King, on the advice of one of his ministers] decided in view of the above-mentioned demands not to receive Count Benedetti any more, but to have him informed by an adjutant that His Majesty had now received [from Leopold] confirmation of the news which Benedetti had already had from Paris and had nothing further to say to the ambassador. His Majesty suggests to Your Excellency that Benedetti's new demand and its rejection might well be communicated both to our ambassadors and to the Press. |

Bismarck interpolated and changed some of the telegram to make it sound like Count Benedetti told the king to "drop dead." Then he released it to the German newspapers. Thanks to the lightning-like speed of the telegraph, the story was in all the French newspapers the next day.

Bismarck knew that Napollyon wanted war . . . but Prussia was not going to be the aggressor and fire the first shot.... He knew that the amended telegram would be like waving a red flag before the Gallic bull.

Sure enough, as soon as the telegram appeared in the French newspapers, the cry in the streets of Paris was: "On to Berlin."

France declared war on Prussia on July 19, 1870

The French imagined that they would be marching through the streets of Berlin in a matter of weeks....In reality, the Prussians conducted a lightning-like war . . . and they were marching through the streets of Paris in February 1871.

Moltke was among the first European generals to entrust his entire correspondence to the electric telegraph, cutting notification times and, in two instances, the Danish War of 1864 and the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, synchronizing the opening moves from his office in Berlin. In an age when most field commanders felt chained by the telegraph ("there is nothing worse than campaigning with a wire in your back," an Austrian general had famously complained in 1859), Moltke at once recognized the potential of the telegraph to coordinate vast "encirclement battles" or Kesselschlachten by multiple pincers. (Wawro, The Franco-Prussian War, p. 47).

Marshal François Achille Bazaine commanded the French armies and Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke commanded the Prussian forces.

Marshall Bezaine (1811–1891) in Mexico. |

|

Helmuth von Moltke (1800–1891). |

The French army was exhausted after the debacle in Mexico but they were still supremely confidant of victory. They were not aware that Prussia had studied the U.S. Civil War very carefully and the telegraph and railroad were part of their 2 pronged lightning-like war strategy.

Prussian

cavalry attacking French guns

at the Battle of Mars-la-Tour. |

|

Napollyon III as a prisoner of Bismarck. |

They adopted the telegraph for rapid communications and the railroad for rapid movement of troops.

While the Prussian's adopted President Lincoln's use of the telegraph and railroad, they did not adopt his maxim of . . . with malice toward none, with charity for all.

The newly united German empire held on to the conquered territory of Alsac-Lorraine. Gallic pride was severely wounded by their defeat and round 2 began in August 1914.

The liberation of Roma was the result of the Franco-Prussian War!!

The war was a disaster for France, and the French troops upholding the Pope's temporal power at Roma had to be withdrawn.

After over 1000 years of waiting, the Italians finally arrived at their moment of destiny.

Liberating general Raffaele Cadorna. |

|

Italian troops entering Rome at Porta Pia. |

Pope Pius IX, who had just declared himself INFALLIBLE, was hurled from his lofty throne and Rome became the capital of united Italy.

The Russian Black Sea Fleet and the Franco-Prussian War!!

In 1854, Great Britain and France—normally bitter enemies—united with the Terrible Turks in a war of aggression against Russia....It was called the Crimean War and lasted from 1854 to 1856.

This was the first war in which the telegraph was used....Russia was defeated and had to withdraw her fleet from the Black Sea and the Mediterranean.

When Austria was determined to come to the aid of France, the great Russian Emperor warned them to stay out:

Even before the French defeats, the Czar's declared intention of matching any Austrian declaration of war with one of his own had enabled Moltke to summon the three army corps standing along the Austrian frontier to join the armies in the Palatinate. The news of Wissembourg created in Vienna an uneasiness which only victory could have dispelled; and by 10th August the Austrian army had abandoned all the military preparations which it had half-heartedly begun. (Howard, The Franco-Prussian War, p. 120).

Without Austrian help against the Prussians, France was doomed.

Czar Alexander II (1818–1881). Czar of Russia from 1855 to 1881. |

|

|

Russia's moment of retribution came during the Franco-Prussian War when Russia reintroduced her fleet to the Black Sea:

Bismarck's balancing act involved reining in Moltke while staving off British and Russian attempts to include the Franco-Prussian War termination in a general European conference on outstanding diplomatic questions like Russia's recent re-militarization of the Black Sea. Seizing upon the distraction of the Franco-Prussian War, Russia in November 1870 had begun rebuilding its naval bases in the Black Sea, a clear violation of the treaty that had ended the Crimean War fourteen years earlier. To avoid a war with the Russians to reimpose the terms of the Treaty of Paris, the British hoped to revive France as an ally as quickly as possible, which clearly necessitated a quick end to the Prussian invasion and mild peace terms. To buy time, Bismarck summoned a preemptive conference of great powers on 3 January 1871. Now more than ever he needed to end the Franco-Prussian War, and reacted furiously when he learned that Moltke was negotiating with Trochu behind his back, to secure Trochu's surrender while Moltke's field armies ratcheted up their efforts against Chanzy and Bourbaki. (Wawro, The Franco-Prussian War, p. 290).

This war turned out to be victory even for France which soon thereafter declared a Republic with liberté, égalité, fraternité.

The war was also a great victory for Russia after her disastrous defeat in the Crimean War.

Vital Links

References

Howard, Michael.The Franco-Prussian War. The Macmillan Company, New York, 1962.

Morse, Edward Lind. Samuel F. B. Morse. His Letters and Journals. (In 2 volumes), Houghton Mifflin Co., New York & Boston, 1914.

McDonald, Saga of the Seas, The Story of Cyrus Field and the Laying of the First Atlantic Cable, Wilson-Erickson, New York, 1937.

Nickles. David Paul. Under the Wire: How the Telegraph Changed Diplomacy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MASS, 2003.

Wawro, Geoffrey. The Franco-Prussian War. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. 2003.

Copyright © 2020 by Patrick Scrivener