THE FIRST ATOMIC EXPLOSION IN THE NEW WORLD TOOK PLACE AT PORT CHICAGO NEAR SAN FRANCISCO ON JULY 17, 1944. |

The U.S. Navy became the Cnfederate Navy during the Presidency of Roosevelt the Rebel in 1901. Amazing, "Deak" Parsons was born in the very same year that the Confederates hijacked the U.S. Navy.

If you can believe it, the rebels dropped a NEVER-TESTED gun-assembly atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Officially, the only nuclear device they tested was the implosion type bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945.

The inventor of the gun-assembly device was Navy Captain William "Deak" Parsons. So confident was he of his invention that he felt that no test was necessary

|

CSA Captain Parsons was in charge of the technical part of producing the bomb, while J. Robert Oppenheimer was in charge of the theoretical physics behind a nuclear chain reaction.

|

At Los Alamos, Deak lived in the house opposite the Oppenheimers:

The house opposite the Oppenheimers' would go to another top administrator, Captain William ("Deak") S. Parsons, an affable and experienced Annapolis graduate whom Groves brought in to run interference between the scientists and the military, and who would become assistant laboratory director. As one of the few men at Los Alamos with explosives training, he was also head of the Ordnance Division and would be in charge of dropping the bomb. His wife, Martha, was a "navy brat"–an admiral's daughter. She had lived on bases all her life and so adapted quickly to Los Alamos. Despite being military people, the Parsons immediately endeared themselves to the scientists with their big, informal house parties. (Conant, 109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos, p. 94).

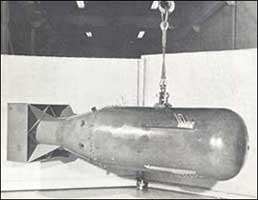

Captain Parsons was the inventor of the gun-assemby device for "Little Boy." He armed the bomb during the flight to Hiroshima and was in charge of dropping the atomic bomb on the city.

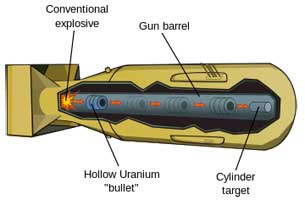

The first bomb was a gun-type assembly device

The first bomb was designed to work like the barrel of a gun. Deak Parsons was trained in naval gunnery, so he was completed committed to this type of bomb.

|

|

|

In the gun-assembly method, a sub critical mass of uranium-235 (the projectile) is fired down a cannon barrel into another sub critical mass of U-235 (the target), which is placed in front of the muzzle. Both gun and target are encased in the bomb. When projectile and target contact, they form a critical mass which explodes.

If the firing is not fast enough, the neutrons emitted by the projectile will begin interacting with the target before the contact and before the mass has become critical. In this case, a pre-detonation occurs.

The gun-type atomic bomb was tested on July 17, 1944

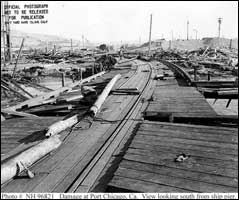

The first known nuclear explosion occurred on the night of July 17, 1944, in Port Chicago, just north of San Francisco.

|

The armed forces of the U.S. were highly segregated in 1944. The only positions open for blacks were in menial jobs. In Port Chicago, they loaded ammunition onto ships 7-days a week, in three round-the-clock 8-hour shifts.

All the overseers were Simon Legree type officers, while the backbreaking work was left to the black sailors.

The atomic explosion was visible over 200 miles away but the official line was that ammunition exploded. The commanding officer of the Alamogordo air base had been provided weeks before with a news release in which each word had been numbered for security. Groves now ordered the release to be distributed at once. A copy of it was rushed to the AP office in Albuquerque. The wire service story that appeared in a modest half-column on the front page of the Albuquerque Tribune that afternoon carried the lead:

An ammunition magazine, containing high-explosives and pyrotechnics, exploded early today in a remote area of the Alamogordo air base reservation, producing a brilliant flash and blast which were reported to have been observed as far away as Gallup, 235 miles northwest. (Lamont, Day of Trinity, p. 250).A plane HAPPENED to be flying over the area at that time:

The devastation was so complete that 320 sailors were killed instantly.An Army Air Force plane HAPPENED to be flying over at the time. The copilot described what he saw: "We were flying the radio range from Oakland headed for Sacramento. We were flying on the right side of the radio range when this explosion occurred. I was flying at the time and looking straight ahead and at the ground when the explosion occurred. It seemed to me that there was a huge ring of fire spread out to all sides, first covering approximately three miles–I would estimate it to be about three miles–and then it seemed to come straight up. We were cruising at nine thousand feet above sea level and there were pieces of metal that were white and orange in color, hot, that went quite a ways above us. They were quite large. I would say they were as big as a house or a garage. They went up above our altitude. The entire explosion seemed to last about a minute. These pieces gradually disintegrated and fell to the ground in small pieces. The thing that struck me about it was that it was so spontaneous, seemed to happen all at once, didn't seem to be any small explosions except in the air. There were pieces that flew off and exploded on all sides. A good many stars and [it] looked like a fireworks display." (Allen, The Port Chicago Mutiny, p. 63).

320 sailors were killed instantly!!

The devastation to the town of Port Chicago was complete. Many were blinded by the brilliant flash of light that accompanied the explosion:

|

This nuclear test showed the deadly destructiveness of even a low yield nuclear weapon:

Everyone on the pier and aboard the two ships and the fire barge was killed instantly–320 men, 202 of whom were black enlisted men. (Only 51 bodies sufficiently intact to be identified were ever recovered). Another 390 military personnel and civilians were injured, including 233 black enlisted men. This single stunning disaster accounted for more than 15 percent of all black naval casualties during the war.(Allen, The Port Chicago Mutiny, p. 64).

2 ships were literally torn to pieces:

The E. A. Bryan was literally blown to bits–very little of its wreckage was ever found that could be identified. The Quinalt Victory was lifted clear out of the water by the blast, turned around, and broken into pieces. The stern of the ship smashed back into the water upside down some five hundred feet from where it had originally been moored. The Coast Guard fire barge was blown two hundred yards upriver and sunk. The locomotive and boxcars disintegrated into hot fragments flying through the air. The 1,200 foot-long wooden pier simply disappeared.(Allen, The Port Chicago Mutiny, p. 64).

Deak Parsons was most anxious to see the result of the nuclear research at Los Alamos.

Deak Parsons visited Port Chicago after the explosion!!

Soon after the explosion, Deak Parsons left Los Alamos and visited Port Chicago to see how his invention worked:

Parsons could not avoid the extra responsibilities that went with being the senior naval officer at Y, but many of the tasks that he took on were self-imposed. In July 1944 he did not have to personally investigate the explosion of two ammunition ships at Port Chicago, northeast of San Francisco. It was, however, something he felt he had to see for himself. As the chief planner for the military delivery of an explosion of unprecedented size, he recognized the Port Chicago disaster as a chance to examine the effects of the largest explosion ever to occur in the United States.

On 20 July, accompanied by a Los Alamos officer and a scientist, Parsons joined his brother-in-law Capt. Jack Crenshaw (a member of the official inquiry into the cause) at Mare island, and they went together to the Port Chicago site. There they observed what had happened when over 1, 500 tons of high explosives and additional tons of shells, smokeless powder, and incendiary clusters exploded in a harbor: the USS E. A. Bryan "fragmented and widely distributed"; the USS Quinalt (waiting to be loaded) torn into large pieces; three hundred and twenty men killed (of which two-thirds were African-American seamen loading ammunition); nothing left of the pier within four hundred feet of the detonation; a wood-frame shop demolished; freight cars buckled. Of the persons killed, all but five were at the center of the explosion. All of the serious damage took place within a one-mile radius. (Christman, Target Hiroshima: Deak Parsons and the Creation of the Atomic Bomb, p. 154).

Within a week of the successful test of his gun-type bomb, captain Parsons was promoted to the rank of commodore.

Major reorganization at Los Alamos in August 1944!!

Even though the nuclear explosion at Port Arthur was a spectacular success, the scientists at Los Alamos soon discovered that there was not enough uranium-235 available for many more bombs and plutonium would not work in the gun-assembly device:

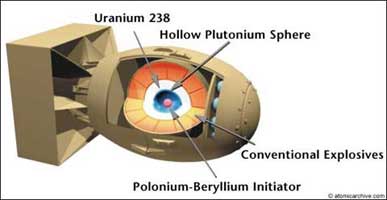

Emilio Segré was perplexed. The handsome Italian physicist, a colleague and great friend of Enrico Fermi, was one of the discoverers of plutonium, and he felt he knew the element and its bizarre properties as well as anyone in the world. (Hard as glass under some conditions, plutonium was as soft as plastic under others; even stranger, it actually contracted when heated). But in midsummer of 1944, as he conducted tests on a tiny sample from the prototype pile at Clinton, Segré found something that seemed to stand his knowledge on its head. His tests showed that the sample contained unmistakable traces of a new plutonium isotope whose atomic weight, at 240, was one unit greater than the Pu-239 with which he and everyone else had been working.

The discovery was chilling. If Pu-240 emitted alpha particles on its own, Pu-239 would be "contaminated" by an excess of unattached neutrons. Because a gun-type bomb–a sort of adaptation of a reliable standard model then in wide use in other bombs–would be triggered by a mechanism that was relatively slow-moving, the plutonium would detonate in advance of the trigger, rendering the bomb a harmless fizzle. Only in an implosion bomb–in which, theoretically at least, the mechanics were so fast that the explosion would take place before the contaminating isotope had time to cause predetonation–could the crippling effects of Pu-240 be overcome. Segré's next round of tests confirmed his worst fear: Pu-240 was indeed an emitter of alpha particles. The chances of using plutonium successfully in a gun-type weapon were now virtually zero.(Lawren, The General and the Bomb, p. 171).

The OLD RELIABLE gun-assembly bomb was kept on standby as work proceeded on a new design called the implosion bomb.

|

Deak Parsons, general Groves, and J. Robert Oppenheimer worked feverishly on the new implosion type bomb. By July, 1945, it was ready for testing.

|

After the nuclear blast, newspapers reported that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Parsons flew with his nuclear bomb all the way to Hiroshima!!

Even though he was a "NAVY" man, Parsons FLEW with his bomb all the way to Hiroshima. He had given birth to the MONSTER and was not about to let it out of his sight until the mission was accomplished:

|

Commodore Parsons left Tinian Island in the early morning hours of August 6, 1945, bound for the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

|

This "never tested" bomb exceeded all expectations and the entire city of Hiroshima was virtually wiped off the map.

Luis Alvarez flew in the observation plane over Hiroshima!!

Deak Parsons arrived over the city of Hiroshima just before 8:15 AM on August 6, 1945. The bomb was dropped by parachute and exploded a few thousand feet above the city. He left nothing to chance and obviously it worked perfectly as he had planned.

Mushroom cloud rising over Hiroshima, Japan. |

|

As in the case of Port Chicago, almost everything was destroyed for about a mile in every direction. |

Only a few concrete buildings were left standing as almost everything was destroyed within a radius of 1 mile:

The blast that followed the explosion destroyed thousands of houses, burning most of them. Of 76,000 buildings in Hiroshima, 70,000 were destroyed. Fire broke out all over the city, devouring everything in its path. People walked aimlessly in eerie silence, many black with burns, the skin peeling from their bodies. Others frantically ran to look for their missing loved ones. Thousands of dead bodies floated in the river. Everywhere there was "massive pain, suffering, and horror," unspeakable and unprecedented. Then the black rain fell, soaking everyone with radiation. Those who survived the initial shock began to die from radiation sickness. According to one study conducted by the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 110,000 civilians and 20,000 military personnel were killed instantly. By the end of 1945, 140,000 had perished. (Hasegawa. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, p. 180).

Luiz Alvarez flew in an observation plane over Hiroshima to measure the killing power of the atomic bomb.

Luis Alvarez in front of the Great Artiste in a flak jacket. |

|

Alvarez (top right) on Tinian with Harold Agnew (top left), Lawrence H. Johnston (bottom left) and Bernard Waldman (bottom right). |

General Groves said that the area totally devastated was about the same area as Port Chicago.

The area devastated at Hiroshima, was 1.7 square miles, extending out a mile from ground zero. The Japanese authorities estimated the casualties at 71,000 dead and missing and 68,000 injured. (Groves, Now It Can Be Told, p. 319).

Commodore Parsons was in no way surprised . . . because the results confirmed to the first test at Port Chicago . . . only the destructive force of the bomb was far greater.

The atomic bomb was designed to keep the Russians from invading Japan!!

The assassination of President Roosevelt by MI6 was supposed to save Hitler and the Third Reich from a Russian invasion. Likewise, the atomic bomb was supposed to force a quick Japanese surrender before Russia had a chance to declare war on Japan.

Stalin and Truman at Potsdam. |

|

Stalin, Truman, and Churchill at Potsdam. In the background can be seen the sinister admiral Leahy. |

By July 24, Truman was fully appraised of the success of the Trinity test, and he had a new super weapon that he could use to blackmail the Soviets. He casually mentioned the weapon to Stalin, who appeared nonplussed:

At 7:30 PM on July 24, the eighth plenary session of the Big Three meeting took a recess. As the participants were walking around, Truman approached Stalin without his interpreter and casually confided: "We have a new weapon of unusual destructive force." Stalin showed no interest; at least so it seemed to the president. Truman remembered: "All he said was that he was glad to hear it and hoped we would make 'good use' of it against the Japanese." Stalin's nonchalant reply fooled everyone who witnessed the exchange, including Truman. Everyone thought Stalin did not understand the significance of the information. (Hasegawa. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, p. 154).

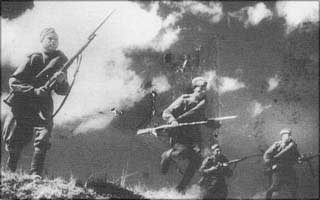

Stalin was not fooled however, he had his spies. and he knew all about the atomic bomb:

Stalin responded quickly to what he perceived to be secret American maneuvers. At Potsdam he had told Truman that the Soviet Union would enter the war by the middle of August, but Antonov had told the American Chiefs of Staff that the Soviets would be ready to join the war in the last half of August. In all likelihood, the date of attack had remained some time between August 20 and 25, as set before the Potsdam Conference. With American possession of the atomic bomb and Truman's manipulation of the Potsdam ultimatum, however, Stalin changed the timetable for the Soviet attack. It appears that while still in Potsdam, he ordered Marshal Vasilevsky to move up the operation by ten to fourteen days. (Hasegawa. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, p. 177).

Stalin had to order an all out assault on Japanese held Manchuria and the Kurile Island—without any regard to casualties....By the time the Japenese surrendered, the Russians were barred from occupying any part of the Japanese mainland by threat of the use of atomic weapons.

Soviet troops crossing the Manchurian border on August 9, 1945. |

|

Marshal Vasilevsky (1895–1977) commanded the Soviet Far Eastern Front. |

The Russians never occupied the main Japanese islands and they had absolutely no say in the future of Japan. That is why the corrupt "divine" emperor was allowed to stay and Japan did not become a REPUBLIC!!

The formal surrender of Japan finally came on September 2, 1945. Thanks to Truman, Japan was not forced to sign a peace treaty with Russia and the two countries are still officially in a state of war.

Vital Links

References

Alperovitz, Gar. The Decision to Use the Bomb. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1995.

Allen, Robert L. The Port Chicago Mutiny: The Story of the Largest Mass Mutiny Trial In U.S. Naval History. Warner Books, New York, 1989.

Christman, Al. Target Hiroshima: Deak Parsons and the Creation of the Atomic Bomb .Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1998.

Groves, Leslie R. Now It Can Be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. Harper & Brothers, New York, 1962.

Groueff, Stephane. Manhattan Project: The Untold Story of the Making of the Atomic Bomb. Little, Brown & Co., New York, 1967.

Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and Surrender of Japan. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MASS, 2005.

Lawren, William. The General and the Bomb. A Biography of General Leslie R. Groves. Dodd, Mead & Co., New York, 1988.

Lamont, Lansing, Day of Trinity. Atheneum, New York, 1965.

Norris, Robert S. Racing for the Bomb. Steerforth Press, South Royalton, Vermont, 2002.

Rhodes, Richard. The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon & Schuster, New York, 1986.

Copyright © 2015 by Patrick Scrivener