Usury Article from the Catholic Dictionary.

|

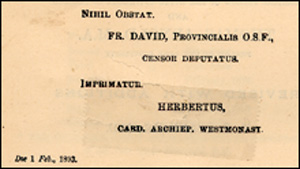

Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur means that this is Rome's official teaching on usury. |

A Catholic Dictionary by William E. Addis and Thomas Arnold, M.A. London 1905. In 1830 the Congregation of the Holy Office, with the approval of Pius VIII., decided that those who regarded the fact that the law fixed a certain rate of interest as in itself a sufficient reason for taking it, were "not to be disturbed." This principle is now accepted throughout the Church, though the Holy See has given no positive decision on the matter. Even the laws restraining the clergy from taking interest are entirely obsolete. (The Modern View) |

Usury. Usury in its wider signification, means all gain made by lending. This is a sense which usury often has in the classics, and so understood usury occurs whenever a man lends capital at interest. Now, however, usury signifies unjust gain on a loan, unjust because not justified by the loss, risk, etc., of the lender or the advantage to the borrower, or because the amount of gain is exorbitant. In this latter case usury is forbidden both by the natural law and by the Bible. It is always unjust, and its wickedness is aggravated when advantage is taken of the needs of the poor to secure usurious interest. But we shall see presently that both in the Old Testament and for a long time in Christian legislation little distinction was made between the two kinds of interest. The laws of the Old Testament on the subject had a more important influence on Christian feeling, so that something must be said about the former here.

(1) Usury in the Bible.— Public loans and the humane spirit of the law in Christian nations have taught us to draw a clear line between lawful and usurious interest; but in the ancient world, as it is in the East at this day, interest was always usurious. The Egyptian law contented itself with prohibiting interest which was more than 30 per cent (Diodor. Sic. i. 79); the laws of Menu permitted an interest of 18 or even 24 per cent (see the reference in Smith's Bible Dictionary, article Usury), and 12 per cent is, or was till quite lately, a minimum rate in the East. Partly, no doubt, for this reason, partly because in an agricultural nation like Israel loans were only asked by those whose need put them at the creditor's mercy, partly to encourage kindness towards the poor, the Mosaic law prohibits lending at interest. The most ancient code (Exod. xxi.-xxviii.) prohibits lending at interest to poor Hebrews. Deut. xxiii, 20 forbids interest to be taken from Hebrews generally; Levit. xxv. 35-37 repeats the precept of Exodus, forbidding also interest in kind.

Lending at interest generally is reprobated in the strongest terms in Ps. xv. 5, Prov. xxviii. 8. Nehemias, after the exile, restored the observance of the law against taking interest from Hebrews, and made the usurers restore the “hundredth part" of the money (i.e. “centesimae usurae," 1 per cent. a month= 12 per cent. a year; 2 Esdr. v. 11). The New Testament gives no definite rule on the subject, though of course the spirit of Christ's words, "Give to him that asketh thee" (Matt. v. 42) excludes lending at interest.

(2) Usury in the Church.— The moneylender's trade presented much the same aspect in the Roman State as in the old Eastern world. Loans were still usually made to the needy who could not protect themselves. The "usura centesima" (12 per cent.) was under the later Republic and the Empire the legal rate of interest, which was due every month (i.e. 1 per cent. a month), so that Ovid very naturally calls the Calends "swift," and Horace "sad." This accounts for the feeling of the Church on the matter down to modern times.

(a) The Fathers are unanimous in regarding all interest as usury, and, therefore, as a species of robbery. Their general opinion was that the prohibitions in the Old Testament bound Christians, and that in a more stringent form, since the taking of interest from strangers had only been tolerated among the Jews for the hardness of their hearts. Tertullian ("Adv. Marc." iv. 24, 25), Cyprian ("Testimon." iii. 48), Ambrose ("De Tobia" throughout, see especially 14 and 15), Basil (in Ps. xiv), Jerome (in cap. xviii. Ezech.), Chrysostom (in Matt. Hom. lvi. al. lvii), Augustine ("De Bapt. contr. Donat." iv. 9, in Ps. xxxvi.), Theodoret (in Ps. xiv. 5), in their condemnation of interest appeal, or at least add a reference, to the Old Testament. Other Fathers, probably from mere accident and for the sake of brevity, omit any such appeal—e.g. Apollonius (apud Euseb. "H. E." v. 18), Commodian ("Adv. Gent. Deos," 65), Lactantius ("Inst." vi. 18), Epiphanius (in the "Exposit. Fid." at the end of the "Haer." n. 24), Augustine (Ep. 153). These passages are all explicit. Tertullian, e.g. (foeneris se. redundantiam quod est usura"), Ambrose ("quodcunque sorti accidit "), Jerome ("usuram appellari et superabundantiam quicquid illud eat, si ab eo quod dederit, plus acceperint"), define usury as taking interest; the word Epiphanius employs is "taking interest;" "it is unjust," says Lactantius, "to take more than one gave."

(b) Conciliar and Papal Laws.—From early times the clergy were forbidden, under penalty, to take interest. So Canon. Apost. 44, Council of Arles A.D. 314 (c. 12), of Nicaea (c. 17), Laodicea (c. 4), Leo I. (Ep. 5, "Ad Episc. Campan."), Council in Trullo (c. 10). Not that taking interest was considered by these authorities permissible in laymen; such a thing, says Leo, is lamentable in the case of any Christian, and so of course specially reprehensible in clergymen. The mediaeval canon law extended the penalties to laymen Thus the Second Lateran Council, A.D. 1139 (c. 3, lib. v. Decret. tit. 19, c. 3, c 7), condemns usurers to excommunication and deprives them of Christian burial. Clement V. in the Council of Vienne (Clem. lib. v. tit. b, De Usuris, c. Ex gravi) declares it heresy to maintain pertinaciously that usury is no sin. It is plain from St. Thomas (2, 2, qu. lxxviii.) that all taking of interest was still regarded as usury. Further, Alexander III. (lib. v. Decret. tit. 19, c. ti) decides a case proposed by the Bishop of Genoa. The merchants of that city used to sell spice above the market value, agreeing to wait a stated time for payment. The Pope replies that such a contract, unless there was some doubt whether the market price might not rise or fall in the meantime, though not strictly speaking usurious, was sinful.

(c) The Modern View.—It

became more and more evident that commerce could not exist without a rate

of interest, and reflection showed many just grounds on which a moderate

rate could be exacted. Such are the risk to the lender, the loss to which

be is put by the want of capital with which he might trade, the fruit

which the money yields, &c. The law can remove many of the dangers

of usury by fixing a legal rate, and the poor are now just the persons

who would suffer most, were all interest prohibited. It was long, however,

before opinion adapted itself to new circumstances. Luther consistently,

and Melanchthon with some hesitation, stood where the Fathers and canonists

had stood before them. (See the quotations in Herzog, art. Wucher.)

Bossuet represents Calvin as the first theologian who propounded the modern

distinction between interest and usury, and this seems to be true, so

far at least as writing goes, though, according to Funk ("

Zins and Wucher," p. 104), Eck and Hoogstraten

had defended the same distinction at Bologna. Bossuet himself maintains

the old doctrine as of faith (" Traite de 1'Usure" in vol. xxxi.

of the last edition of his works), and this though, he was fully aware

of the arguments on the other side. He rejects as sinful the charge of

interest on the general ground that the lender could have used the capital

he lends in trade, though, very, inconsistently, he allows interest to

be charged if the lender has foregone a particular and definite gain,

which he had in prospect. Benedict XIV. in his encyclical to the Italian

bishops, "Vix pervenit," A.D. 1745, condemned the doctrine that

interest might be taken, merely on the ground of a loan, however low the

rate of interest, and although the borrower might be ever so rich and

have profited by using the money in trade, though he leaves the questions

about the accidental or extrinsic reasons for taking interest, the risk,

loss of profit, &c., quite unsettled. Further, this Pope, according

to Ballerini (loc. cit. p. 615), allowed books defending the modern view

to be dedicated to him. Keen controversy on the point among Catholics

had arisen during that century, and the work of the famous Scipio Maffei

(1675-1755) on the laxer side ("dell' impiego del danaro ")

had attracted great attention. In 1830

the Congregation of the Holy Office, with the approval of Pius VIII.,

decided that those who regarded the fact that the law fixed a certain

rate of interest as in itself a sufficient reason for taking it, were

"not to be disturbed." This principle is now accepted throughout

the Church, though the Holy See has given no positive decision on the

matter. Even the laws restraining the clergy from taking interest are

entirely obsolete. Gury accepts the position tolerated in the decree

of the Sacred Congregation, and argues that the State has power in certain

cases to transfer the property of one subject to another. No doubt. But

where is there the faintest proof that the State means to exercise this

power in the case, and to transfer the interest from the pocket of the

borrower to that of the lender? We may add that the Fathers, in the places

quoted above, expressly, deny that the State-law makes usury lawful, Ballerini,

rejecting Gury's explanation argues that the words "loan" (mutuum),

&c., imply spontaneous liberality, but that interest may be taken

if there has been a previous contract to that effect. It is scarcely necessary

to answer that the Fathers and Schoolmen meant much more than a truism

like this—viz. that a man must not require interest if

he professes to lend without it. Later on, Gary (ii. p. fill) seems to

give the true reason. The ancient world believed that money was barren,

and the Schoolmen inherited this principle from Aristotle. Experience

proves that money, far from being barren, "produces fruit and multiplies

of itself" ("fructum producit et multiplicatur per se,"Gury,

loc. cit.), and a man may justly take 5 per cent. for money which is well

worth that to the merchant, bank, railway company, &c., who receive

the loan.

(Herzog, "Encycl. fur Prot. Theol." art. Wucher, gives useful citations from the Reformers. Smith and Cheetham; Funk's work "Zins and Wucher," Hefele, " Beitrage"and Concil."vol. i., have also been used. But for exhaustive learning and clear statements of the points at issue we have seen nothing comparable to Bossuet's "Traité de I'Usure.")

Editor's Note

The "usura centesima" of the Roman Empire was so called becaue the capital doubled in 100 months or about 8 years.

References

Addis, William E., & Arnold, Thomas, M.A., A Catholic Dictionary, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., London, 1905.

Murray, J.B.C., The History of Usury, Philadelphia, 1866.