|

1946 Atlanta Constitution Atom Bomb Articles

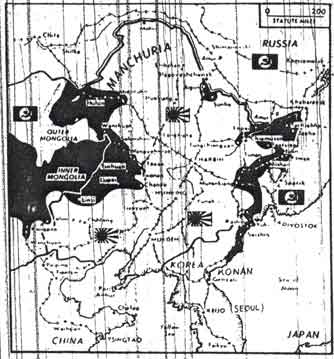

Actual Test Was Success Japan developed and successfully tested an atomic bomb three days prior to the end of the war. She destroyed unfinished atomic bombs, secret papers and her atomic bomb plans only hours before the advance units of the Russian Army moved into Konan, Korea, site of the project. Japanese scientists who developed the bomb are now in Moscow, prisoners of the Russians. They were tortured by their captors seeking atomic "know-how." The Konan area is under rigid Russian control. They permit no American to visit the area. Once, even after the war, an American B-29 Superfortress en route to Konan was shot down by four Russian Yak fighters from nearby Hammung Airfield. I learned this information from a Japanese officer, who said he was in charge of counter intelligence at the Konan project before the fall of Japan. He gave names, dates, facts and figures on the Japanese atomic project, which I submitted to United States Army Intelligence in Seoul. The War Department is withholding much of the information. To protect the man that told me this story, and at the request of the Army, he is here given a pseudonym, Capt. Tsetusuo Wakabayashi. The story may throw light on Stalin's recent statement that America will not long have a monopoly on atomic weapons. Possibly also helps explains the stand taken by Henry A. Wallace. Perhaps also, it will help explain the heretofore unaccountable stalling of the Japanese in accepting our surrender terms as the Allies agreed to allow Hirohito to continue as puppet emperor. And perhaps it will throw light new light on the shooting down by the Russians of our B-29 on Aug. 29, 1945, in the Konan area. When told this story, I was an agent with the Twenty-Fourth Criminal Investigation Department, operating in Korea. I was able to interview Capt. Wakabayashi, not as an investigator or as a member of the armed forces, but as a newspaperman. He was advised and understood thoroughly, that he was speaking for publication. He was in Seoul, en route to Japan as a repatriate. The interview took place in a former Shinto temple on a mount overlooking Korea's capital city. The shrine had been converted into an hotel for transient Japanese en route to their homeland. Since V-J Day wisps of information have drifted into the hands of U.S. Army Intelligence of the existence of a gigantic and mystery-shrouded industrial project operated during the closing months of the war in a mountain vastness near the Northern Korean coastal city of Konan. It was near here that Japan's uranium supply was said to exist. This, the most complete account of activities at Konan to reach American ears, is believed to be the first time Japanese silence has been broken on the subject. In a cave in a mountain near Konan, men worked against time, in final assembly of genzai bakuden, Japan's name for the atomic bomb. It was August 10, 1945 (Japanese time), only four days after an atomic bomb flashed in the sky over Hiroshima, and five days before Japan surrendered. To the north, Russian hordes were spilling into Manchuria. Shortly after midnight of that day a convey of Japanese trucks moved from the mouth of the cave, past watchful sentries. The trucks wound through valleys, past sleeping farm villages. It was August, and frogs in the mud of terraced rice paddies sang in a still night. In the cool predawn Japanese scientists and engineers loaded genzai bakudan aboard a ship in Konan. Off the coast near an inlet in the Sea of Japan more frantic preparations were under way. All that day and night ancient ships, junks and fishing vessels moved into the anchorage. Before dawn on Aug. 12 a robot launch chugged through the ships at anchor and beached itself on the inlet. Its passenger was genzai bakudan. A clock ticked. The observers were 20 miles away. This waiting was difficult and strange to men who had worked relentlessly so long who knew their job had been completed too late. OBSERVORS BLINDED BY FLASH The light in the east where Japan lay grew brighter. The moment the sun peeped over the sea there was a burst of light at the anchorage blinding the observers who wore welders' glasses. The ball of fire was estimated to be 1,000 yards in diameter. A multicolored cloud of vapors boiled toward the heavens then mushroomed in the stratosphere. The churn of water and vapor obscured the vessels directly under the burst. Ships and junks on the fringe burned fiercely at anchor. When the atmosphere cleared slightly the observers could detect several vessels had vanished. Genzai bakudun in that moment had matched the brilliance of the rising sun in the east. Japan had perfected and successfully tested an atomic bomb as cataclysmic as those that withered Hiroshimo and Nagasaki. The time was short. The war was roaring to its climax. The advancing Russians would arrive at Konan before the weapon could be mounted in the ready Kamikaze planes to be thrown against any attempted landing by American troops on Japan's shores. It was a difficult decision. But it had to be made. The observers sped across the water, back to Konan. With the advance units of the Russian Army only hours away, the final scene of this gotterdammerung began. The scientists and engineers smashed machines, and destroyed partially completed genzai bakudans. Before Russian columns reached Konan, dynamite sealed the secrets of the cave. But the Russians had come so quickly that the scientists could not escape. This is the story told me by Capt. Wakabayashi. Japan's struggle to produce and atomic weapon began in 1938, when German and Japanese scientists met to discuss a possible military use of energy locked in the atom. No technical information was exchanged, only theories. In 1940 the Nisina Laboratory of the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research in Tokyo had built one of the largest cyclotrons in the world. (Cyclotrons found in Tokyo by the invading Yanks were destroyed). THOUGHT ATOMIC BOMB RISKY The scientists continued to study atomic theory during the early days of the war, but it was not until the Unites States began to carry the war to Japan that they were able to interest the Government in a full-scale atomic project. Heretofore, the Government had considered such a venture too risky and too expensive. During the years following Pearl Harbor, Japan's militarists believed the Unites States could be defeated without the use of atomic weapons. When task forces and invasion spearheads brought the war ever closer to the Japanese mainland, the Japanese Navy undertook the production of the atomic bomb as defense against amphibious operations. Atomic bombs were to be flown against Allied ships in Kamikaze suicide planes. Capt. Wakabayashi estimated the area of total destruction of the bomb at one square mile. The project was started at Nagoya, but its removal to Korea was necessitated when the B-29's began to lash industrial cities on the mainland of Japan. "I consider the B-29 the primary weapon in the defeat of Japan" Capt. Wakabayashi declared. "The B-29 caused our project to be moved to Korea. We lost three months in the transfer. We would have had genzai bakudan three months earlier if it had not been for the B-29." The Korean project was staffed by about 40,000 Japanese workers, of whom approximately 25,000 were trained engineers and scientists. The organization of the plant was set up so that the workers were restricted to their areas. The inner sanctum of the plant was deep in a cave. Here only 400 specialists worked. KEPT IN DARK ON EACH OTHER'S WORK One scientist was master director of the entire project. Six others, all eminent Japanese scientists were in charge of six phases of the bomb's production. Each of these six men were kept in ignorance of the work of the other five. (Names of these scientists are withheld by Army censorship). The Russian's took most of the trained personnel prisoner, including the seven key men. One of the seven escaped in June, 1946, and fled to the American zone of occupation in Korea. U.S. Army Intelligence interrogated this man. Capt. Wakabayashi talked to him in Seoul. The scientist told of having been tortured by the Russians. He said all seven were tortured. Capt. Wakabayashi said he learned from this scientist that the other six had been removed to Moscow. "The Russians thrust burning splinters under the fingertips of these men. They poured water into their nasal passages. Our Japanese scientists will suffer death before they disclose their secrets to the Russians," he declared. Capt. Wakabayashi said the Russians are making and extensive study of the Konan region. When Edwin Pauley of the War Reparations Committee, inspected Northern Korea, he was allowed to see only certain areas, and was kept under rigid Russian supervision. On Aug. 29, 1945, an American B-29 headed for Konan with a cargo of food and medical supplies, to be dropped over an Allied prisoner of war camp there. Four Russian Yak fighters from nearby Hammung Airfield circled the B-29 and signaled the pilot to land on the Hammung strip. PILOT REFUSES; REDS FIRE Lt. Jose H. Queen of Ashland, KY., pilot, refused to do so because the field was small, and headed back toward the Saipon base, to return "when things got straightened out with the Russians." Ten miles off the coast the Yak fighters opened fire and shot the B-29 down. None of the crew of 12 men were injured, although a Russian fighter strafed but missed Radio Operator Douglas Arthur. The Russian later told Lt. Queen they saw the American markings but "weren't sure." because sometimes the Germans used American markings and they thought the Japs might too. This was nearly two weeks after the war ended. Capt. Wakabayashi said the Japanese Counter Intelligence Corps at least a year before the atom bombing of Hiroshima learned there was a vast and mysterious project in the mountains of the eastern part of the United States. (Presumably the Manhattan project at Oak Ridge, Tenn). They believed, but were not sure, that atomic weapons were being produced there. On the hand, he said, Allied Intelligence must have know of the atomic project at Konan, because of the perfect timing of the Hiroshimo bombing only six days before the long-scheduled Japanese naval test. Perhaps here is the answer to moralists who question the decision of the United States to drop an atomic bomb. The Japanese office, the interpreter and I sipped aromatic green tea as Capt. Wakabayashi unfolded his great and perhaps world-shaking story. His eyes flashed with pride behind the black-rimmed glassed. When the interview ended, he ushered us to the door and bowed very low.

News to Me Groves says of Japanese Atom Bomb. Washington, Oct. 2 (UP). Major General Leslie Groves, Chief of the atom bomb Manhattan project said Wednesday night when informed of reports that Japan explored a test A-bomb three days before surrender. "I would be very much interested if the story were true." "It's all news to me." War Department officials declined immediate comment on the story carried by the Atlanta Constitution which said that the writer, recently returned from duty with a criminal investigation detachment, had given his information to the American Army Intelligence Unit in Seoul, Korea. Dr. Carl T. Compton, President of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told a Senate Committee a year ago that Japan had been trying to develop an A-bomb but that the effort failed for two reasons: Japanese physicists reached mistaken conclusions, B-29 attacks demolished the laboratory where such experiments were being conducted. American forces entering Japan after the surrender of the nation discovered a cyclotron (an atomic splitting device used by laboratories) and destroyed the instrument. Many military experts concerned with atomic development contend that Germany was far more advanced than any other nation except the American, British and Canadian teams in the race to produce an A-bomb. German scientists were known to have made substantial strides in research before the military collapse of the Reich. Indeed it is recorded that non-Nazi scientists who fled Germany contributed valuable knowledge to the research which ended in production of the first A-bomb in New Mexico Japan Sought Peace Through Russia Nearly Month Before First A-Bomb. New York, Oct. 2---(UP). America's submarines and pre-atomic bombers had Japan so thoroughly whipped that the Emperor sought peace through neutral Russia nearly a month before Hiroshimo's destruction. Long before that, Japan had periodically tried to make peace with China. The inside Japan story is told in "The Lost War" published Wednesday by Alfred A. Knopf. The author is Masuo Kato prominent Japanese correspondent for 20 years. Kato was in Washington for Domei News Agency when the war started, and was repatriated. When Domei was dissolved after the war, the American educated Kato became managing editor of the Kyodo News Agency. Writing in traditional newspaper important things first style, Kato starts his book with this lead paragraph: The thunderous arrival of the first atomic bomb at Hiroshima was only a coup de grace for an empire already struggling in particularly agonizing death throes. The world's newest and most devastating of weapons had floated out of the summer sky to destroy a city at a stroke, but its arrival had small effect on the outcome of the war between Japan and the United States. CITES BUNGLING. Kato assured Allied readers, already aware of their own "bureaucratic bungling" during the war, that the totalitarian Japan's bungling was far worse. He describes incessant Army-Navy-civilian jealousy, the drafting of vital skilled workers for frontline duty, and poor planning in almost all phases of the war effort. Even Cabinet members were kept from knowing Allied progress against Japan. He records a little bitterly the Japanese Army's absurd effort to hide the truth even when the nation was all but crushed. Because of this he believes no people could hate its leaders more than the Japanese people hated their military by the spring of 1945. Revealing that Emperor Hirohito finally overruled the military clique that had dominated him throughout the war, Kato relates the surrender developments in these words: Japan's diplomatic maneuvering for peace dated from the negotiations by Russia in April 1945, that her neutrality agreement with Japan had lost its significance in view of the war between Japan and Russia's allies. KONOYE SEE EMPEROR Prince

Konoye was received in audience by the Emperor on July 12, 1945, and

ordered to go to Moscow. On the following day the Foreign Office notified

Moscow that the Emperor was desirous of peace and that Konaye would

be sent to Russia in that connection. No reply was forthcoming but it

was hoped by the Japanese Government that Premier Stalin and Foreign

Minister Molotov would transmit to Britain and the Unites States at

the Potsdam Conference Japan's desire to discuss peace.

|

||||||||||||